The Virgin Islands’ Recovery to Development Plan promises to make the territory “near carbon neutral.”

But what does that mean exactly, and how would it get done?

The Beacon recently discussed the topic with former Bhutan Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay.

Along with Suriname, Bhutan — a small, landlocked Himalayan nation sandwiched between China and India — is one of only two countries in the world that are widely recognised as being carbon neutral, meaning that they remove at least as much carbon from the atmosphere as they emit.

Since the 1970s, Bhutan has measured its success in large part by gauging “gross national happiness” rather than gross domestic product. Mr. Tobgay attributed its environmental policies in part to that philosophy, but during a March visit to the VI he explained that his country faces grave threats from global warming.

The leader, who served as prime minister from 2013 to 2018, often uses Bhutan as an example to encourage larger countries to keep their promise to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees over pre-industrial levels — as more than 190 nations pledged when they adopted the Paris Agreement in 2015.

But even if that goal is met, he said, climate change will have devastating effects on his country and much of the rest of the world.

IS IT POSSIBLE TO IDENTIFY A DATE WHEN BHUTAN BECAME “CARBON NEUTRAL”?

I don’t know when they measured it. The definition of carbon neutral is you absorb more carbon than you emit. Because we’ve always had a lot of forest coverage, we’ve always been carbon neutral. We hardly emit. Our forests alone absorb three times the amount we emit.

In addition to that, all our energy is hydroelectric and renewable. So what this means is we have the possibilities of exporting clean energy, and that offsets the need for carbon-based fuel.

The credit goes to all of our leaders in the past, but really our kings, because they have put environment on the top of the agenda from the 1960s. They’ve always said that our job is custodians of the environment, and as a result we are a biodiversity hotspot. We are custodians of countless secrets in our dense jungles that may yet yield medical solutions to the world.

But to really highlight the importance of carbon neutrality, and to highlight the contribution of Bhutan — a very small country that has not contributed to global warming and climate change — I coined the phrase “carbon negative.”

IT IS OFTEN SAID THAT THE VIRGIN ISLANDS IS DISPROPORTIONATELY AFFECTED BY CLIMATE CHANGE. THOUGH WE DON’T DO A LOT TO CAUSE IT, WE’RE AFFECTED BY IT MORE THAN MOST OTHER COUNTRIES BECAUSE OF RISING SEA LEVELS, LARGER STORMS AND OTHER EFFECTS. WOULD YOU SAY THAT BHUTAN IS IN A SIMILAR POSITION?

Absolutely. Let me put it this way. When I saw Hurricane Irma batter the BVI and the Caribbean islands, I was torn apart. It has to be climate change, though some people say it is not and “Why blame everything on climate change?” Regardless, even if there is a small possibility that it is climate change, we need to be careful.

![]()

So I could see BVI and the Caribbean struggling. But closer to home, there is this group of islands called the Maldives. And there the people are literally drowning. Sea levels, if they rise a little bit, their whole home — their islands — are going to be drowned. It’s going to be no more. Similarly with many other islands. I remember watching this interview in the Maldives, and the president was talking about his islands disappearing. And it struck a chord with me. We need to take climate change seriously.

Recently, scientists have said that glaciers in the Himalayas are melting. Well, we know they’re melting, but they’ve also said even if the commitments made in Paris are achieved — very bold commitments, which is to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels — even then our glaciers are not going to be safe. They are going to melt.

What does that mean? Our whole livelihood is going to change: the whole Himalayas and the whole Hindu Kush region. Not just Bhutan. Without the glaciers, there’s going to be a lot of flash floods. Because we are in the mountains, we have precious little farming land. They are going to be washed away.

Floods are going to be unpredictable and many. And the floods there are going to be dangerous because many of our lakes are formed because of glaciers, and when glaciers melt, these lakes are going to grow bigger. Some of the lakes are going to merge, and the moraine dams — the natural dams that have held the lakes in the past — are going to be breached. This is going to wreak havoc. So this is really dangerous stuff.

ARE YOU ALREADY SEEING THESE EFFECTS?

Yes. We’ve seen glaciers recede. Incidentally, we’ve seen the number of glaciers increase in Bhutan. Sounds like good news right? It’s terrible news! What this means is what used to be big glaciers are melting and dividing. And so we have lakes we have had to manually dredge at 5,000 metres above sea level where we don’t have roads.

We have floods. These floods are going to flood downstream — India and China — and that’s going to raise the ocean levels, and Maldives is going to disappear even faster, even if the 1.5 target is kept. So Maldives is threatened now by the glaciers.

Global warming by itself, because it’s warm, is going to melt our glaciers. But it gets even more dangerous, because at that temperature it will not snow there. It will rain. And water will melt the ice even faster. So it’s not just the temperature. What makes things even worse is the pollution. Carbon particles are already collecting in our mountains, and these carbon particles because of their colour attract heat. It’s all going to add up to a dangerous situation.

So I’m applauding all nations, hoping that they keep their commitment and really encouraging everybody to do their part to achieve the targets of the Paris agreement. But now we’re fully aware that that’s going to be too little too late.

IN THE VIRGIN ISLANDS AND IN OTHER CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES, IT IS EXPENSIVE AND POLITICALLY DIFFICULT TO PASS CLIMATE CHANGE MITIGATION MEASURES. FOR EXAMPLE, WE’RE IN A PRETTY GOOD PLACE TO HARNESS GREEN ENERGY WITH SUN, WIND AND THE LIKE. BUT IN THE VI WE HAVEN’T GOTTEN FAR. WE’RE STILL BURNING FOSSIL FUEL FOR SOME 98 PERCENT OF OUR ENERGY. HOW DID BHUTAN MANAGE TO PUT IN PLACE SUCH POLICIES?

Every country has its own challenges. In Bhutan our challenge is we don’t have fossil fuel. That’s a challenge, yeah? Who doesn’t want oil? But because of that we have had to use our rivers to generate electricity, and that is an opportunity. In that respect we have been lucky.

A challenge is that we have a small population — we have only 700,000 people — and human resources is a challenge. We don’t have enough people. The opportunity is that because we have a small population and even though it is agrarian, it is very natural — small landholding farming — farming that is very natural and sometimes subsistence.

So on the one hand where you have an economy that is very small with a population that is very small, the opportunity is that we don’t have to destroy our forest. Naturally people will not go and destroy our forest.

But to use the opportunities and to address the constraints in wise manner, you need enlightened leadership. And we’ve been fortunate because we have our kings. As early as the seventies when environment wasn’t a thing — nobody was concerned — our king refused to chop down our forests and sell the timber; refused to go into large-scale mining; refused to allow unregulated tourism; focussed on renewable energy; protected our forests.

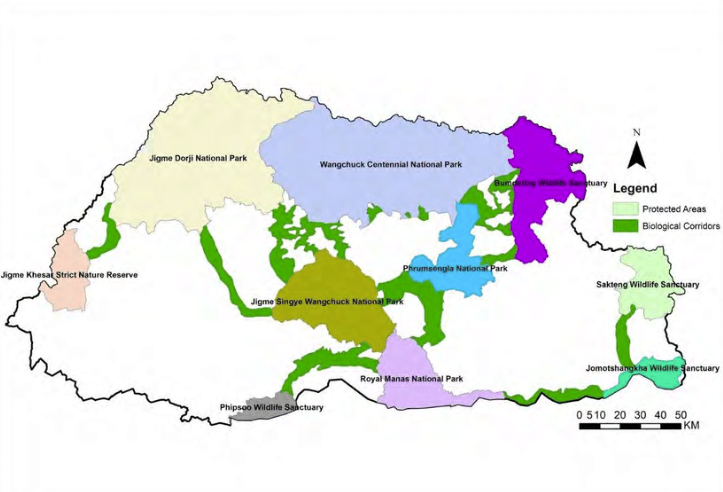

That’s why 72 percent of our country is under forest cover. And that in itself is something I think is a big achievement for a poor country. But what’s more important is that 72 percent is ancient forest. It’s untouched. And within that we have a system of parks. So half our country is designated as nature reserves, national parks, wildlife sanctuaries. And by law you cannot touch them. Our constitution requires that a minimum of 60 percent of our country is under forest cover.

THIS SORT OF THING IS EXPENSIVE. IN BHUTAN, THE GOVERNMENT REVENUE IS ABOUT $400 MILLION PER YEAR FOR SOME 700,000 PEOPLE, AND IN THE VI IT’S ABOUT $300 MILLION FOR ABOUT 30,000 PEOPLE. SO IT SEEMS THAT FUNDING MUST BE VERY TIGHT IN BHUTAN. HOW DO YOU FUND CLIMATE CHANGE MITIGATION AND PREPARATION THERE?

It must be prioritising what’s important. Bhutan is one of the poorest countries in the world. Our economy is just $2.5 billion. Our GDP per capita is $3,500. Here it is almost $50,000. And you have a lot going for you here in the BVI. I know that many people here are very, very environmentally conscious and active. And I know that many in the BVI are similarly concerned. Your government is very transparent; you’ve done a great job in tourism and finance. So a lot is going for you.

In Bhutan, economically, we’re not doing great. We are still one of the poorer countries in the world. That said, that economy is sustainable and there’s a fair degree of dignity among people. Education is free, health care is free and all that. So it’s leading to a lot more equity than in many other poorer countries.

How do you manage? I suppose it’s leadership. And when I say leadership I’m not talking about politicians like me. I’m talking about the leadership exercised by our kings; the guidance and moral leadership that is still available with the kings in spite of parliamentary democracy. The whole country looks to the king.

IN THE VI, WE HAVE A CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION POLICY THAT SETS OUT VARIOUS GOALS, BUT WE’RE FAR BEHIND ON MOST OF THEM. I UNDERSTAND THAT BHUTAN HAS A NATIONAL ADAPTATION PLAN. HOW IS IT GOING WITH IMPLEMENTING THAT?

We’ve had a long history of protecting our environment and having mitigation measures, and so this is not new. So for countries where this is new — I don’t know when BVI started… .

2012 WAS WHEN WE GOT THE POLICY HERE.

So this is new. And suddenly with an adaptation plan like this you have to make sacrifices. It’s difficult. It’s new.

In Bhutan, we’ve had a national environmental commission for decades now, whose job is to look after the environment. In addition to that, the overall development philosophy in Bhutan is called gross national happiness. And this philosophy really makes it very clear that protecting the environment is very, very important; that our ecology is very important; that it must be nurtured.

Gross national happiness, started by our king, really started in the 1970s. So we have a history of being really aware of our responsibilities to Mother Nature.

But this is all in a modern context. Traditionally, our type of spirituality required that we are respectful to nature, whether it is water bodies like springs and rivers, lakes; certain trees and cliffs and caves.

BECAUSE BHUTAN IS A MAJORITY BUDDHIST COUNTRY?

Yes. We believe that deities reside there. We don’t allow mountaineering. In the early seventies when mountaineering was allowed, people sat down and appealed to the king; they discussed with the National Assembly. The people of Bhutan who lived in those areas said, “Our deities live there, so you can’t desecrate them by having people climb up their palaces.” That’s just an example. That’s why we have the world’s tallest unclimbed mountain.

DO YOU REMEMBER WHEN CLIMATE CHANGE STARTED TO BECOME PART OF THE PUBLIC DIALOGUE IN BHUTAN?

We were way ahead of the world in terms of conserving the environment and respecting the environment and having policies in place to preserve the environment just for the sake of that. Because it is our responsibility to take care of the environment. That has been going on for decades. In terms of concern for climate change, it’s global. So when global discussion happened, that’s when we started thinking a lot more about it.

IS THERE ANY ADVICE YOU WOULD GIVE THE VI?

I can’t give any advice, because you have many more experienced, more wise people here. But I want to visit and I want to enjoy BVI and learn as much as possible. And if anything, like some say: Think globally, act locally. You must point fingers to the world at large. You must! And you must criticise when necessary. But we must all act in our own little domains. In our own localities. In our own homes. If you can do that, then I think we’re that much more closer.

Interview conducted, condensed and edited by Freeman Rogers.