As sea levels continue to rise in the coming decades, entire communities in the Caribbean and elsewhere probably will be forced to relocate even if large nations keep the pledges they’ve made to reduce carbon emissions and limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, according to a recent report that paints one of the bleakest pictures yet of the consequences of climate change.

The Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, published on Sept. 24 by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, outlined grim predictions for the 65 million people living in small island states.

Even if the global community coalesced today to quickly cut greenhouse gas emissions, small islands like the Virgin Islands will still see “extreme sea level events” — which historically occurred once per century — sweeping the coastlines annually by 2050, the study predicted.

Islands can take steps to adapt to these changes — early warning systems, sea walls, and mangrove restoration, for example — but for low-population, high-risk areas like the VI the only option might one day be relocating entire populations.

“Small island states face rising seas that threaten habitability of their homeland and the possibility of losing their nation-state, cultural identity and voices in international governance,” the report states, adding, “In some situations the most appropriate responses may involve relocation of critical services and, in some cases, communities. And for some populations, migration away from their homeland may become the only viable response.”

Expected impacts

The report, which was compiled by more than 100 authors from 36 countries, references about 7,000 scientific publications to assess the projected impacts of climate change on the ocean and cryosphere — a term encompassing ice sheets, ice caps, glaciers, snow and permafrost.

The impacts expected to affect the vast majority of low-lying islands include sea level rise, ocean acidification and a shrinking cryosphere, bringing risks of permanent submergence of land; more frequent and more intense flooding; coastal erosion; loss of coastal ecosystems; salinisation of soils and ground and surface water; and impeded drainage.

The effects are also exacerbated by local factors like coastal urbanisation, degraded mangroves and coral reefs, a “lack of long-term integrated planning, changing consumption modes, conflicting resource use, and socioeconomic inequalities,” the authors found.

While the depth of scientific evidence might stand out, the stark warnings in the report are not new, according to Charlotte McDevitt, the executive director of the non-profit Green VI.

“I don’t think it’s anything we don’t know, to be honest. It’s all the normal stuff,” Ms. McDevitt said. “Well, it’s not normal: It’s all the terrifying stuff. I suppose it’s just that they’ve got more evidence on it now.”

Though the VI Cabinet approved a “Green Paper” in July outlining long-promised environmental legislation to promote the sustainable development of the VI, some experts say that government isn’t doing enough to stem the existential risks the territory faces.

Tourism

The IPCC, an intergovernmental body of the United Nations, outlines how sea level rise threatens to inundate homes, infrastructure, landscapes, harbours and airports, endangering the tourism industry that many countries in the Caribbean rely on.

It points out that the three 2017 major Caribbean storms — Harvey, Irma and Maria — caused tourism industry losses of about $2.2 billion in the VI, Dominica, and Antigua and Barbuda, with recovery costs estimated at $6.8 billion.

Climate mitigation policies on air travel in tourists’ countries of origin might also decrease tourism flows.

Sarah Penney, deputy director of Green VI, said the territory’s efforts to bring in high volumes of tourists often do not take into account the costs of tourism to the VI’s roads, sewerage system, beaches and oceans.

For example, while the previous government’s $150-$200 million airport expansion proposal might bring in more visitors, it did not take into account the impact of the increased carbon emissions or the costs of mitigating the risks of sea level rise for an airport that sits just above the water, she said.

“If you don’t spend that [money] on issues related to the environment — and really specifically on waste, energy and water — there’s not going to be a place for people to come to,” she said.

Reef systems

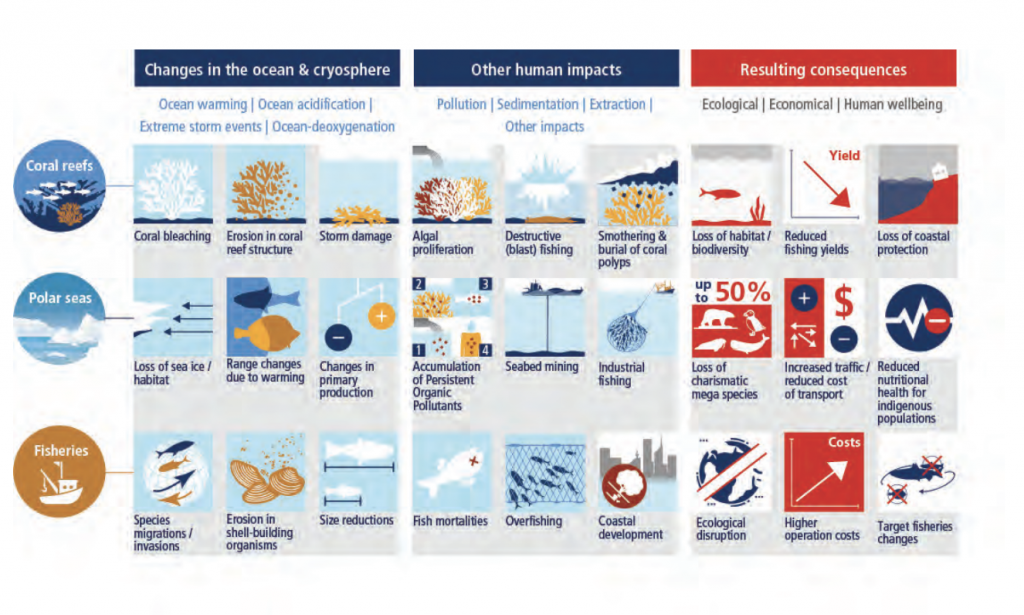

The IPCC report also stated that coral reefs are the marine ecosystem most threatened by ocean-related climate impacts like sea level rise and ocean acidification.

“Almost all warm-water coral reefs are projected to suffer significant losses of area and local extinctions, even if global warming is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius [above pre-industrial levels],” stated the report, adding that the authors had high confidence in this prediction. “The species composition and diversity of remaining reef communities is projected to differ from present-day reefs.”

This decline is projected to endanger the food provision, coastal protection and tourism that the coral reefs provide. Small island states that are highly reliant on seafood will see an elevated risk of nutritional health problems, according to the report.

“This isn’t [just] some global issue,” Ms. McDevitt said. “This is really affecting us.”

The report points out that these damaging effects are exacerbated by human activities.

In the VI, for example, a coral disease spotted in the United States VI and other nearby islands in recent months threatens to decimate coral reefs if it reaches the territory.

Biologist Dr. Shannon Gore, the managing director of the Association of Reef Keepers and principal consultant for the VI-based firm Coastal Management Consulting, said that the territory has seen coral bleaching occurring for years.

“Basically, once those reefs are dying and they start eroding, now you’re losing coastal protection,” she said.

“They’re not productive like they used to be, so they’re not producing the sand that you see on the beaches.”

And scientists say that warmer temperatures, sewage pollution, and disruption from anchors make the coral more susceptible to disease.

Dr. Gore said that the existing $1,000 fine for damaging coral in the VI is too low, and it is rarely levied.

“Every so often you see there’s some boat that’s run aground somewhere in the BVI,” she said, “and it’s kind of like nothing’s ever done.”

Adaptation

The IPCC predicts with “medium confidence” that some island nations will become uninhabitable, pointing out that more than 80 percent of small-island residents live near the coast, “where flooding and coastal erosion already pose serious problems.”

The report also mentions the effects that widespread damage could have on cultural heritage and identity if residents are forced to relocate.

“Retreat may be especially effective, albeit socially, culturally and politically challenging,” it states.

The societal impacts of climate change are complex, and occur over a longer timeline than most governmental decision-making cycles, according to the report.

Coordinating a climate adaptation response is particularly tricky for small islands because of their extreme vulnerability to climate-related risks as well as other factors like inaccessibility, demographic and settlement trends, and land subsidence caused by local activities.

The report also points out that areas like low-lying islands — which face some of the highest exposure to current threats from ocean and cryosphere changes — also face the biggest financial, technological and institutional barriers to adaptation.

Certain adaptation methods like assisted species relocation and coral gardening can be effective when they are community-supported and science-based, but are unlikely to work if global warming exceeds 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the authors found.

While structures like dikes, embankments, sea walls and surge barriers are widely used and effective in reducing damage, they typically are cost-efficient only for urban and densely populated areas and are largely unaffordable for rural and poorer regions, according to the study.

Small islands in particular struggle with maintaining these structures because they lack “adequate funds, policies and technical skills,” the report stated. More cost-effective methods include climate-resilient infrastructure, faster and more effective disaster response, and improved public health and emergency services.

But Dr. Gore said the VI is not doing enough to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change. For example, she said, rules that dictate how near to the shoreline builders can construct new infrastructure has not been updated since 1972.

She added that she would like to see concrete ghuts cleared out and redesigned to absorb more water and prevent flooding, as well as simple measures like building longer-lasting roads so that the tarmac can better withstand heavy rains.

Ms. Penney also pointed to simple measures she said the VI could take to improve the health of its ecosystems, like prohibiting cruise ships from dumping sewage in its waters.

Premier Andrew Fahie called for action on climate change in the House of Assembly on Oct. 17, and praised the remarks made by Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley at the UN Climate Action Conference in September, but offered no specific policy proposals.

“We have the front row seat to the destructive vicious cycle of climate change, which is spurred on by such factors as global warming, rising ocean temperatures and melting of ice sheets, to name a few,” he said, adding, “Regional leaders including myself are using every available forum to bring urgent attention to this situation that places countries like ours at the greatest immediate risk, but greedy capitalists in other so-called more developed countries are paying no heed as they continue to pump pollution and carbon into our atmosphere and oceans.”

Ecosystem restoration

More than 30 small island developing states in their Nationally Determined Contributions submitted to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change advocate for ecosystem-based adaptation measures like mangrove planting and coral reef restoration to address dangers.

However, the IPCC says that there is “limited evidence and low agreement” on the cost-effectiveness of these measures.

There is also a tradeoff in conserving these areas because of their high economic value, which is why they are prime targets for manmade destruction, particularly in small land-scarce areas like the VI, according to the report.

However, these measures do provide benefits like sequestering carbon, boosting tourism income, improving water quality, enhancing fishery productivity, and providing raw materials for fuel, medicine, food and construction, the authors found.

Ms. Penney said that while the VI’s impact on global carbon emissions may be small, measures like planting trees can have an enormous impact on local resilience.

“The more we plant, the cleaner our air is going to be, the more resilient our soil is going to be,” she said. “Our reef life at this point in time is almost as impacted by runoff and silt as it is by rising sea temperatures and viruses.”

Dr. Gore estimated that more than 80 percent of the VI’s wetlands have been filled in since the 1950s, reducing the territory’s ability to absorb floodwater.

“And you wonder why we have flooding: When you have Road Town — probably the majority of that is concrete. There’s nowhere for that water to go except for down and hitting all the low-lying areas,” she said. “So there’s no catchment for that water.”

She recalls that a wetland policy was drafted years ago and shelved because it was seen as a low-priority item.

“At some point nothing’s going to be left,” she said. “We’re not going to have any mangroves. We’re not going to have any beaches. We’re not going to have any reefs. And then what? What are people going to come here to see?”

Indigenous culture

The IPCC also stresses the importance of incorporating local and indigenous knowledge into adaptation methods.

Aragorn Dick-Read, owner of Good Moon Farm on Tortola, incorporates organic farming practices that he’s gleaned from his travels around the Caribbean and the world. He would like to see the VI embrace more climate-resilient indigenous farming and architecture practices from pre-Columbian times.

“The amazing resource we have is this heritage in the Caribbean of a group of Taino and Kalinago and Caribbeans that existed here for thousands of years before the Europeans came, and they survived through really basic principles of building conical roof houses and growing their food underground and respecting their water sources and harvesting from a landscape and a reefscape and a seascape that they considered sacred,” he said. “Nothing of that is really going on anymore.”

Mr. Dick-Read is sceptical that the VI government is sufficiently serious about climate adaptation, calling its policies “antiquated and laughable.”

He pointed to the recent dissolution of the Climate Change Trust Fund board, which saw the membership of all six of its members revoked by the new government on April 24.

“I think it’s just irresponsible governance. The principle of government is to look after the well-being of population,” he said, adding, “The board was basically just a box-ticking exercise. It didn’t have any power.”

Former board chairman Ed Childs said he did not have any updates on the trust fund — which was established by a 2015 law but never funded by the government as promised — and declined to comment further.

The premier told the Beacon last month that a new board still had not been formed, but that government would make a full statement on the matter soon.

The IPCC also predicts social conflict over the response to sea level rise. Several studies show that the people of Caribbean islands most at risk are psychologically unprepared for the massive devastation to come. Research conducted in St. Vincent and the Bahamas suggests that residents see recent extreme weather events as separate from the “distant psychological risk” of climate change, according to the report.

“There is no problem that we’re facing in the BVI that doesn’t correlate or connect to climate change,” Ms. Penney said.

For example, she said, the Isabella Morris Primary School in Carrot Bay is located next to the ocean, and should be redesigned to take sea level rise into account. She added that the ability of VI children to learn effectively will be affected by the quality of the air, food and water in the territory.

To avoid the worst of the potential social impacts, the IPCC report calls for flexible adaptation policies that take into account the uncertainty of sea level rise; that coordinate across “scales, sectors and policy domains;” and that create community spaces for public discussion and conflict resolution.

The VI got such a policy in 2012, when Cabinet adopted a Climate Change Adaptation Strategy that set dozens of two-to-four-year deadlines for long-promised measures like a national development plan, wetland protection, environmental legislation, and an updated building code, among many others.

Missed deadlines

The great majority of those deadlines, however, have come and gone, leaving wide-ranging promises unfulfilled. The environmental legislation pledged in the strategy has itself been promised for more than 15 years.

Currently, the territory’s environmental protection laws are spread out over a patchwork of largely outdated legislation, including the 1985 Beach Protection Ordinance, the 1997 Fisheries Act, and the 2006 National Parks Trust Act. In the early 2000s the newly launched Law Reform Commission drafted a comprehensive environmental management bill that would bring all of the disparate laws together under one umbrella, but the proposed law never reached the legislature.

“A lot of good stuff came out of it, but at the end we also knew all our recommendations were never going to get passed by government, because the laws took the ability to decide away from government,” biologist Clive Petrovic, who sat on a committee that advised on the draft bill, told the Beacon in 2017.

The Green Paper unveiled this year again promises a comprehensive environmental bill, but no draft has been publicised and it is unclear when the effort will move forward. Dr. Gore said that the slow progress is disheartening.

“It’s frustrating for me to see, knowing what’s going to happen and knowing that something could be done,” she said. “And nobody’s listening and nobody wants to do anything.”

Irma’s opportunities

Ms. Penney said that she recalls discussions about the opportunities Hurricane Irma presented to rebuild in a more sustainable way. The VI, she said, has largely failed to take advantage of those opportunities. Ms. McDevitt also holds on to the hope that innovations and adaptive methods will prevent the worst of the predicted outcomes.

“I think we need to act now,” she said.

Ms. Penney added that while government inaction is frustrating, she would like to see more initiative on the part of the private sector, other residents and visitors.

“The whole position that many people take is: ‘Oh, I wish somebody would do something about that,’” she said. “And we just really need to acknowledge that we are somebody.”