In the weeks after Hurricane Irma, the recovery effort roared to life.

With the help of funding and personnel from the United Kingdom and other partners, the Virgin Islands government rushed to clear roads, open ports and restore essential services.

Two years later, the relief workers are gone, a new administration is squabbling with the UK over a proposed loan guarantee, and much of the progress seems to have slowed to a crawl, with some projects apparently stalled altogether.

A major problem appears to be a lack of funding. The public-sector recovery is expected to cost at least $721 million, but that goal is still far away: Though leaders have been tight-lipped on specifics, their intermittent updates suggest that the government may have accessed less than $60 million to date from loans, grants, insurance payouts and donations.

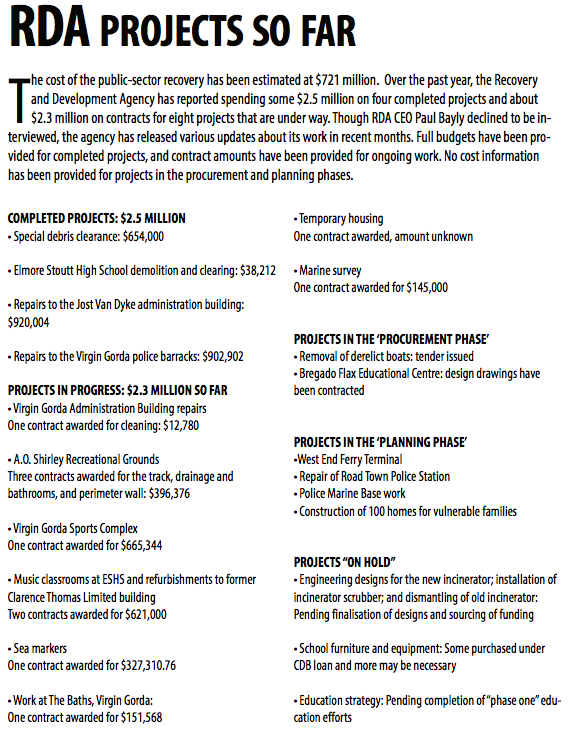

Meanwhile, the Recovery and Development Agency — the body established in April 2018 to lead the recovery effort for five years — has completed only four projects worth about $2.5 million and reported spending just $2.3 million more on contracts for eight others that are in the works.

Premier Andrew Fahie, whose Virgin Islands Party took power in the February election, has defended his government’s efforts and blamed the previous administration for the delays.

But it remains unclear where the rest of the funding will come from, and Mr. Fahie, RDA CEO Paul Bayly and other senior government officials did not grant the Beacon interviews for this article in spite of weeks of requests.

Governor Gus Jaspert, who directed funding questions to the Ministry of Finance when he spoke to the Beacon last month, stressed the dangers of complacency.

“We’re two years on now, and that spirit of action, the spirit of unity, the spirit of fixing things and making things better that we had at the beginning, it’s a challenge that we keep holding onto that,” he said. “Whilst I don’t want everyone to keep remembering about the hurricanes, it is important that we remember … the actions we need to take to secure the territory for the long term.”

Delays’ effects

The effects of recovery delays can be seen in places like Rite Way Supermarket, where police headquarters has been based since late 2017, or behind the supermarket, where high school students are still being housed in the former Clarence Thomas Limited building as a new academic year gets under way.

“My frustrations are that I don’t feel we’re providing an effective service to the community with the police headquarters tucked away in a supermarket,” Police Commissioner Michael Matthews told the Beacon, adding, “We should be far more accessible and far better equipped to respond to the needs of the community.”

Mr. Matthews blamed the delays largely on government bureaucracy.

“I say this regularly to ministers and to the minister of finance himself: There’s too much bureaucracy in the territory and it takes too long identifying an urgent need to getting that need fulfilled,” he said. “When you’re looking at us having this conversation in August 2019, nearly two years since September 2017, a lot of what we’ve got away with, we’ve been lucky, but it shouldn’t have taken that long.”

Besides police headquarters, repairs have not been completed on the Central Administration Building or the Road Town fire station, among others, and construction has not started on major projects like the National Emergency Operations Centre, new high school buildings, or the West End ferry terminal.

There is no main branch of the public library, many hurricane shelters are not ready for a major storm, the Pockwood Pond incinerator is not functioning, and roads that were hastily patched before the February election are falling apart again. Some residents remain homeless, and government said recently that its housing relief programme was underfunded by some $14 million.

Fire station

At the Road Town fire station — which was devastated in Irma — repairs to the upper floor are near completion, but the bottom floor remains damaged. Fire Chief Zebalon McLean said in late July that he could not sit comfortably in a refurbished upper floor while his team suffered poor conditions below.

“I have to admit that it rides on the consciousness emotionally when you see these guys suffering, even till now,” he said. “These conditions, as they have remained, are not fit for habitation.”

Though he said the territory needs a brand-new fire headquarters, he accepts the “honest” reality that the government won’t invest $3 to $4 million for the project now.

“What they decided to do was to do the repairs,” he ex- plained.

In late July, Mr. McLean’s fire officers were putting together a petition to ask for haste in refurbishing the barracks at the station.

“The problem we’re having now is we’re not getting enough funds,” he said.

The budget allocated for the department’s expenses does not cover the cost of repairs, he explained: It includes operational costs for salaries and maintenance.

Currently, four of six fire stations are open in the territory after Rotary helped open the one in East End.

RDA progress

The RDA was established primarily to handle such public-sector recovery efforts.

The agency — which got to work shortly after its CEO arrived in August 2018 — has prioritised 21 “phase one” projects expected to cost about $28.7 million.

So far, it has completed four worth $2.5 million, and reported awarding about $2.3 million worth of contracts for eight others that are currently in operation (see sidebar).

However, the agency’s current finances are unclear: Officials have not said how much is in the VI Recovery Trust, which funds its projects. Like the RDA itself, the trust was established in April 2018 by the VI RDA Act, which requires the trust to receive all recovery contributions, including loans, donations and others.

Moreover, the agency’s “phase one” element represents only a small fraction of the total recovery cost: The Recovery to Development Plan, which the HOA adopted last October, projects a $721 million price tag.

The RDP calls for government to contribute $58.9 million of that cost, and seeks $52.7 million from grants; $221.7 million from loans; $331.4 million from private non-governmental organisations and statutory sources; and $56.7 million from insurance.

Because the premier and other senior officials did not grant interviews, it is unclear how much of that money has been secured, but the great majority appears to remain out of reach even as the RDA is reportedly spending nearly $400,000 per month on operating costs.

Untapped CDB loans

So far, the biggest source of potential funding has come in the form of two loans from the Caribbean Development Bank.

The first, a $65.2 million package, was obtained in December 2017 after the government requested $500 million to rebuild social and economic infrastructure in the transportation, water and sewerage, education and national security sectors. In March 2018, the HOA voted to take another $50 million recovery loan from the regional bank.

However, the government has struggled to access these loans, in part because of CDB requirements that former Edu- cation and Culture Minister Myron Walwyn described as a “vigorous and time-consuming.”

As of December — when the most recent related update was provided — only $15 million had been disbursed from the first loan, most of which was used to fund consultancies for projects like the Central Administration Building, which is slowly being repaired while housing only a fraction of the government offices that used to be there. It is unclear if any more funding from either loan has been disbursed: Though the government has issued some monthly updates on the first package, those reports do not include that information, and the CDB referred questions to government.

During an HOA meeting in May, Mr. Fahie criticised former Premier Dr. Orlando Smith’s administration for its handling of the first loan package.

“I might add that the CDB loan was received — or the approval for it — from December 2017,” he said. “I remember being in the opposition and telling them that they were not ready for that loan; do not take it out. For the whole of 2018 nothing substantial was done to get the loan going until Novem- ber 2018.”

Mr. Fahie added that the CDB conducted a “due-diligence” visit in February to facilitate the transfer of loan funds to the RDA, but there was disagreement about how much the RDA would get.

“The RDA are saying the funds for the loans is under the RDA and there’s a dispute whether the RDA will get 80 percent,” he said. “That is something I’m trying to sort out in the best interests of the people.”

Faced with such challenges, the new government has turned to other measures to complete projects. For example, the ongoing repairs to the Elmore Stoutt High School classroom building were previously to be funded by the first CDB loan, but Mr. Fahie decided to scrap that process and use local funds instead.

Meanwhile, some of the money disbursed from the first loan is being used for tenders and consultancies for efforts related to the National Emergency Operations Centre, the Climate Risk Vulnerability Assessment, the Bregado Flax Educational Centre, and the Eslyn Henley Richiez Learning Centre, according to the most recent monthly update published, from May.

Dr. Smith did not respond to requests for comment.

Grants, donations

Other recovery funding has come from various sources. Besides on-the-ground aid and other early support, the UK government provided a $14 million grant to support the long-term recovery, which has been used to fund the RDA’s operational costs and other projects.

At least $7 million more in gifts, donations and grants has been received or pledged as well, according to government estimates. Insurance payouts also have contributed, including $11.4 million for the Central Administration Building. Other central government facilities were not insured, but some statutory bodies had coverage, including the BVI Airports Authority, which reported receiving $2.2 million as an advance on what it hopes will eventually be a $9.2 million payout.

Meanwhile, a £300 million loan guarantee, first offered by the UK in November 2017 and accepted by the VI government in March 2018, would allow the territory to borrow money more easily and quickly at lower rates, potentially saving tens of millions of dollars and accelerating the recovery process.

But this guarantee has not been accessed yet, and last month Mr. Fahie suddenly signalled that his government might turn it down as he publicly criticised the conditions attached to it.

His complaints echoed previous concerns surrounding the deal. During the HOA debate on the VI RDA Act in March 2018, legislators including government ministers called the conditions of the UK guarantee insulting and said they represented an unacceptable level of colonial control.

At the time, Mr. Fahie, who was then in the opposition, argued that the UK could use the loan guarantee as a “backdoor” way to reassert more significant control by putting the VI in violation of the 2012 Protocols for Effective Financial Management.

Nevertheless, he and other legislators voted to pass the bill, which Dr. Smith said falls in line with international best practice.

Last month, however, Mr. Fahie renewed his criticisms, now as premier. After almost six months in power, he began publicly pushing back against the UK conditions, claiming that the UK government is “demanding the VI basically hand over almost full control of the management of the territory’s finances to the [RDA], which was set up at the request of the UK government.”

The governor denied the allegations, insisting that the UK “has no intention that control of the management of public finances be transferred to the RDA.”

At a public meeting last month, the premier also attacked the RDA, where he implemented a hiring freeze in July, claiming that its operational cost is nearly $400,000 per month.

“Right now in the RDA there’s close to 40 staff but no major project has been done as yet,” Mr. Fahie said. “The BVI government still has to put in the money to help with operating costs and find the money to do the projects.”

The RDA has not publicly responded.

Three stages

In the midst of the acrimony, which continued to escalate this week, the governor told the Beacon that he looks at the recovery in three stages. The first three to six months, he explained, were dedicated to restoring essential services like electricity, water and road- ways. The second stage involved getting the territory’s public safety, education system, and economy running again. The current stage, he explained, is building for the next generation.

“We need to essentially finalise recovery,” the governor said. “We have a dedicated structure through the RDA, we have the offer of financing through the UK loan guarantee, and we have support from other backers. Now is the time to use those structures and develop the BVI.”